A systems-based approach developed at Democracy Fund

In early 2015, serving as founding Program Director of Democracy Fund’s Governance Program, Betsy Hawkings led the development of a “systems map” to illuminate the most impactful points of disruption in Congress and options with the greatest promise for disrupting that dysfunction. The resulting work, which is the intellectual property of Democracy Fund and can be found here, identifies the factors posing the greatest challenges to congressional function, and potential ways to address that dysfunction.

Betsy often speaks to groups seeking to better understand Congress as many find it a helpful tool for discussing and better understanding what ails Congress and how to fix it. The following narrative is from her perspective and reflects the main points of her presentation.

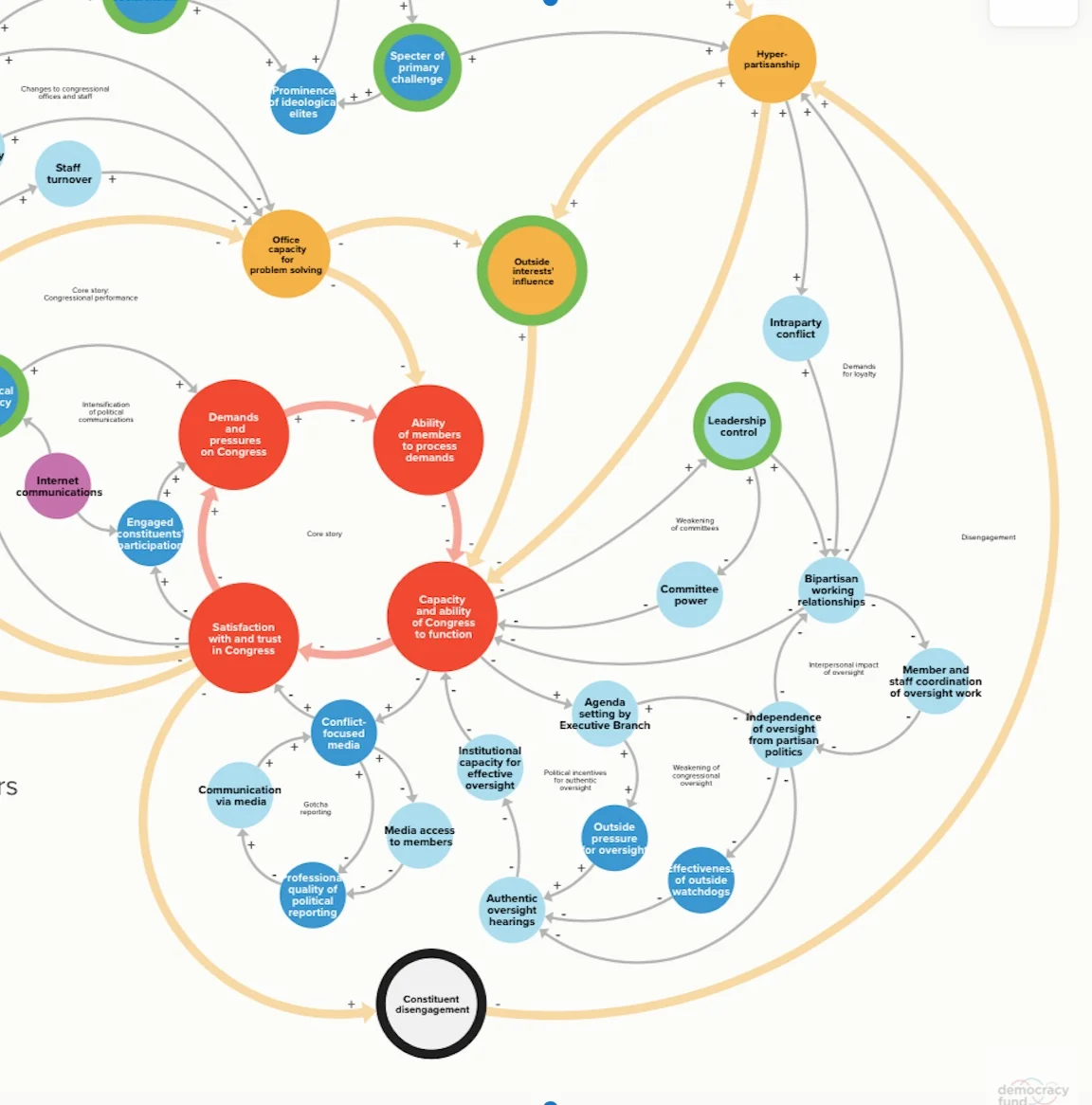

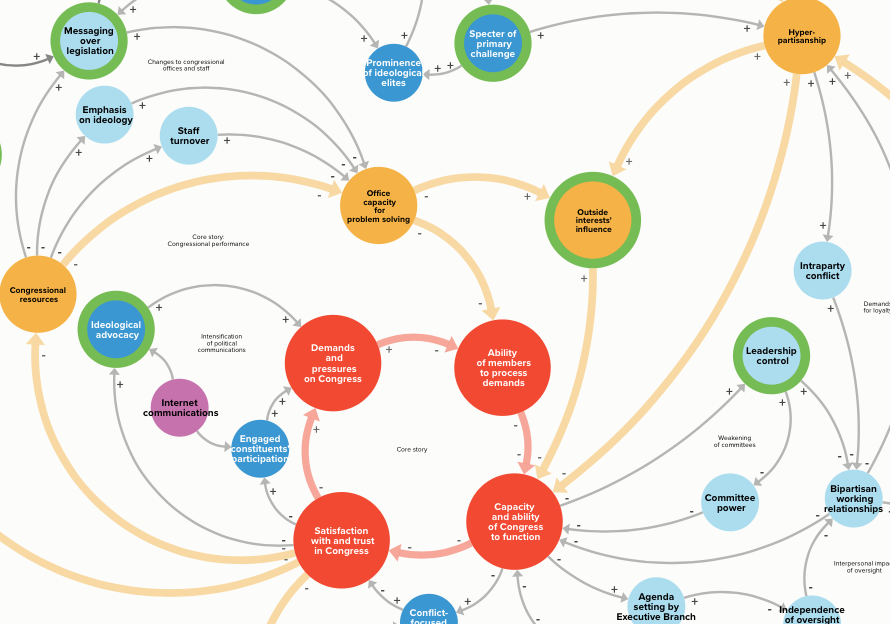

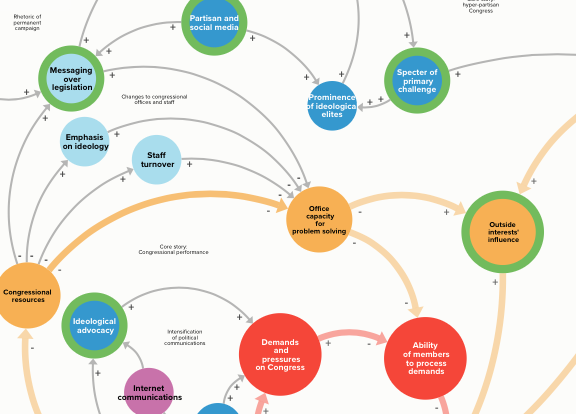

Congress MAP

The map itself can look daunting and a little off-putting at first. It’s helpful to take it section by section as a way of understanding how the drivers of the dysfunction are integrated throughout the system.

SOURCE: Democracy Fund (democracyfund.org/idea/congress-and-public-trust-systems-map/)

Core story

Central to understanding the map as well as Congress’ challenges is what is called the “core story” -- the four red factors in the center of the map.

SOURCE: Democracy Fund (democracyfund.org/idea/congress-and-public-trust-systems-map/)

Historically, this core story described how Congress was intended to function as the Constitution’s First Branch of Government: Throughout our history, the American people have petitioned their government; as those petitions have increased, Congress has processed them; because the system functioned, demands were processed; and -- as we see in the lower left-hand corner -- satisfaction with and trust in Congress was typically strong as a result. While there were exceptions, many people felt confident that, in bringing their demands and petitions, those petitions would be addressed.

Today, the core story describes a “death spiral” of dysfunction; due to several factors, the system has become inelastic and unable to respond. As we see to the left side of the core story loop on the larger map, engaged constituents participate, but their interaction is accelerated by the sheer volume of incoming messages to congressional offices made possible by the Internet, as well as the increase in ideologically-based advocacy, which is driven by hyper-partisanship, and whose messaging is designed to reduce satisfaction and trust in Congress. In fact, those demands and pressures have increased to such a degree that the system struggles to process them; while in 1990 a highly engaged Member office might have received 200 letter and constituent phone calls each week, offices today may receive 10 times that, warranting a significant shift in resources in Members offices while reducing the level of personalization in the responses. Congress’ capacity and ability to function is reduced by the inability to process all that email effectively, and satisfaction and trust in Congress has shrunk as a result.

SOURCE: Democracy Fund (democracyfund.org/idea/congress-and-public-trust-systems-map/)

This failure of performance and trust, in turn, leads to further increase in demands and pressures, exacerbating further the external pressures on the system and in the institution of Congress. As we see in the black circle at the bottom of the map, many people -- mostly those in the political “center” -- are driven to disengage from the system entirely as a result, accelerating the death spiral.

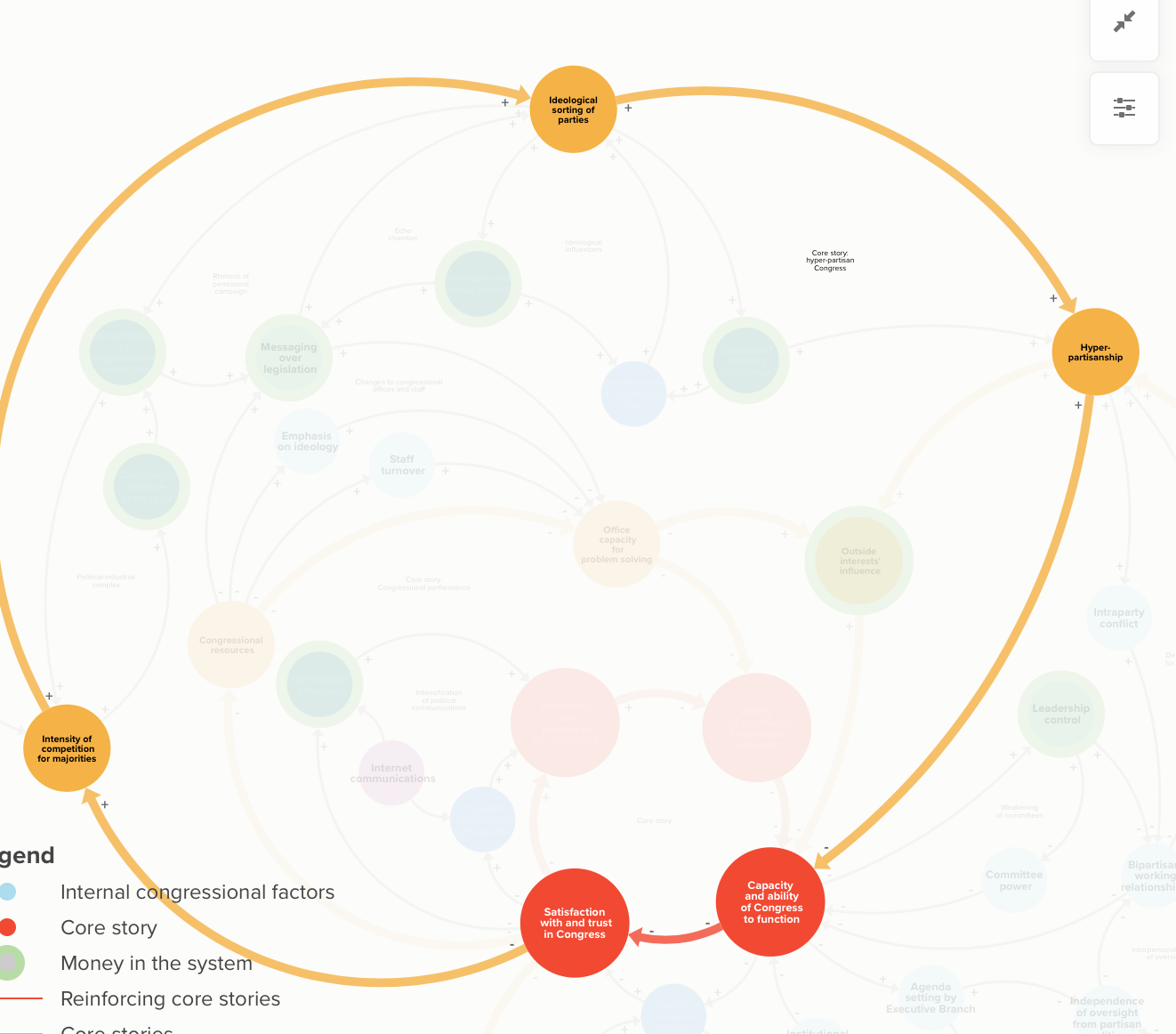

Two Reinforcing Loops

SOURCE: Democracy Fund (democracyfund.org/idea/congress-and-public-trust-systems-map/)

The two larger gold circles on the map, highlighted here, describe the larger forces at play in this acceleration. The outermost yellow circle (above) describes the factors largely “outside” the institution of Congress -- political institutions, partisan influencers and media -- that accelerate hyperpartisanship; the smaller one (below) describes those accelerators that largely take place inside the institution.

SOURCE: Democracy Fund (democracyfund.org/idea/congress-and-public-trust-systems-map/)

Finally, rapidly increasing dissatisfaction with and distrust in Congress leads people to stop participating in the system altogether. This has led to a hollowing out of the electorate, exacerbating and feeding even more hyper-partisanship (below).

SOURCE: Democracy Fund (democracyfund.org/idea/congress-and-public-trust-systems-map/)

Where Does It All Start?

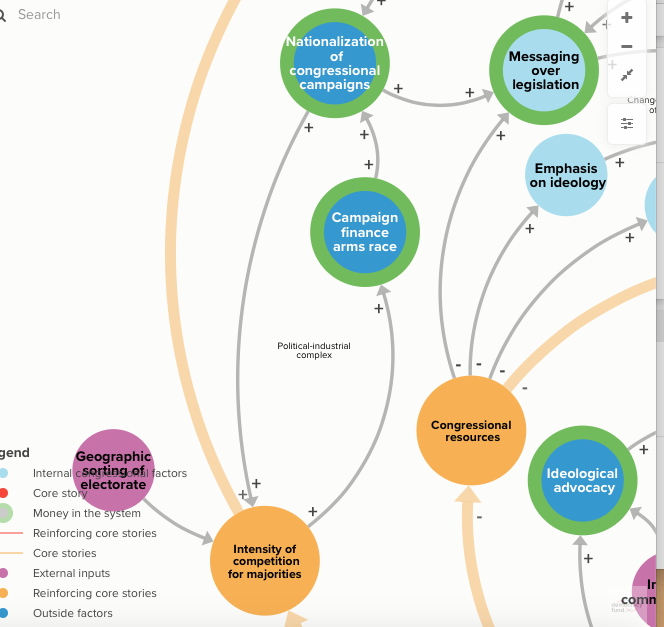

Because this is a system, its elements are interconnected. A good starting point to understand the various factors’ interconnection is with the “intensity of competition for the majority”.

SOURCE: Democracy Fund (democracyfund.org/idea/congress-and-public-trust-systems-map/)

As we see on the map, this competition is exacerbated by the geographic sorting of the electorate, including gerrymandering, but that is by no means the only driver of the intense competition. While many cite the ascent the Republican Majority in 1994 as the catalyst, many also remember the focus on control of the Senate in 1986 -- or, even further back, the fight over Indiana’s “Bloody Eighth” congressional district in 1984, when some believe the Democratic Majority in the House of Representatives unfairly used its power to upend the results of an election. This, in turn, catalyzed the energies of then-new Representatives like Bob Walker and Newt Gingrich to break the chokehold of 40 years of control, and the rest is … history.

Rise of the Political Industrial Complex

Regardless, competitive intensity has increased exponentially since 1994. Attending a Connecticut congressional delegation meeting one week after the 1994 election, those of us still on our post-election high, and anticipating our return in January to the majority for the first time in 40 years, were pretty excited about the huge mountain we had overcome. Congresswoman Rosa DeLauro walked into breakfast, looked around at her Democratic colleagues and said, “What’s wrong with you! Snap out of it! We lost one election. We’ll win the majority back next time.” I realized the flight had not ended; it had just begun.

SOURCE: Democracy Fund (democracyfund.org/idea/congress-and-public-trust-systems-map/)

This intense competition for the majority led to a campaign finance arms race, promoted by what has been dubbed the “political industrial complex.” Money is everywhere in this system; the map circles with green rings the factors where it has the greatest influence. It has grown overwhelmingly over time; as recently as 2002, Betsy’s longtime boss could run a re-election race with roughly $1 million raised by a letter to his donor file. When he last ran in 2008, he needed to raise almost $4 million per cycle, with nearly half coming from PACs. The cost of running that race would be even greater today.

Messaging and Money Built Monolithism

The money chase has only increased the nationalization of congressional campaigns, which feeds the arms race and drive for the majority and also increases the emphasis on messaging over legislation. Party committees exacerbate this emphasis through a network of campaign consultants. Mostly former party committee employees, they form a self-reinforcing loop with other like-minded alumni of the party central committee who are largely still dependent on the party for their livelihood and therefore become reliable messengers of monolithic, one-size-fits-all campaign plans, cookie-cutter messaging and enervated political tactics.

That messaging loop is also fed by an increase in partisan and social media, which is in turn both fed and driven by and ideological sorting of parties and the intensity of competition for majorities. The result: parties of monolithic ideologies and litmus tests in which few would recognize debates that took place in the Republican Party of my youth. Betsy recalls one discussion between her father -- then head of the YGOP of Fairfield County, Connecticut -- and his Senator, then-Republican Lowell Weicker -- regarding US involvement in Vietnam. Her father, a Korean War-era Air Force vet, thought criticism of the war (or our country, ever) unpatriotic and said so at a YGOP meeting where the senator had come to voice his opposition to the War and growing concern about President Nixon. The meeting ended with Weicker (standing 6’8”) fending off my dad (who was 5’9”) after Dad took several swings at the Senator! More importantly, the conversation would not happen at all today.

SOURCE: Democracy Fund (democracyfund.org/idea/congress-and-public-trust-systems-map/)

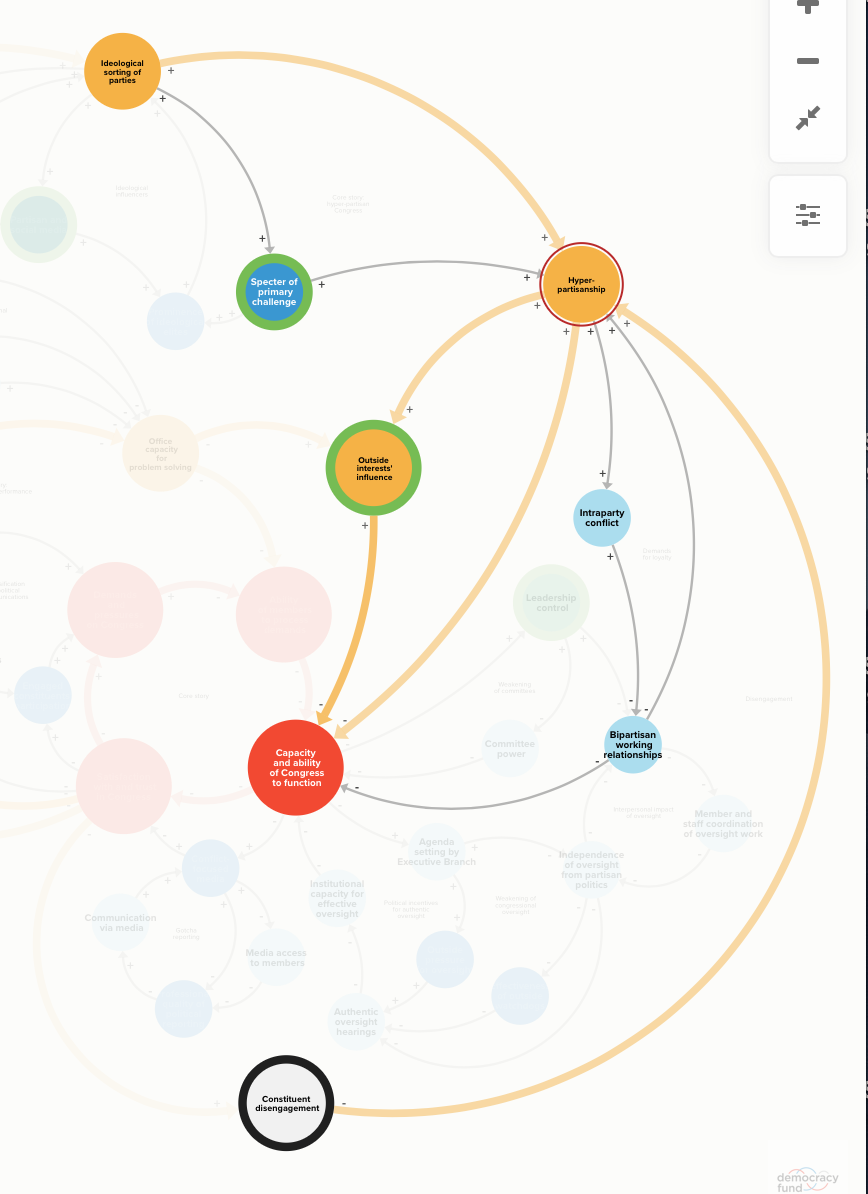

This ideological sorting also increases the specter of primary challenges feared by members of both parties. Primaries enforce monolithic policy positions, feed the prominence of ideological elites and further drive that ideological sorting. We all have heard stories of Members who bemoan the failure to “get things done” in Washington, yet when presented with an opportunity to vote for compromise legislation on a major issue explain that “the base won’t let them do that.” So they actually end up voting against the progress their electorate says they want to see. All of this further feeds into increased hyper-partisanship, decreased engagement, increased influence of outside interests and reduced capacity and ability of Congress to function, further feeding dissatisfaction and distrust.

SOURCE: Democracy Fund (democracyfund.org/idea/congress-and-public-trust-systems-map/)

The resulting distrust has a significant domino effect on the day-to-day operation of Congress. The institution struggles ineffectually to respond and gain the upper hand on the inputs it receives, further undermining its own capacity to function. Members then further reduce their own resources, forcing expertise out of the institution as salaries decrease; turnover increases (thanks to reduced resources), and the strength of leadership over the rank-and file increases further, undercutting the average member’s ability to work their will. Because experience and capacity has left both Member and Committee offices, and because party messaging has become more important than how laws are written, party leadership offices have the greatest remaining legislative know-how in the institution, as well as the opportunity and incentive to circumvent the committee process and completely control the legislation produced. They also can control the allocation of party fundraising and spending on individual members’ races, so the incentives to “toe the line” and follow leadership instructions, even if the vote is not directly aligned with the instincts of Members’ own districts or instincts, is very strong.

SOURCE: Democracy Fund (democracyfund.org/idea/congress-and-public-trust-systems-map/)

Increased hyper-partisanship also breeds increased conflict within the parties, undermining the ability of bipartisan working relationships to develop; if the test of purity is loyalty to party above all else, bipartisan collaboration can be viewed as treason and is often discouraged by the same party leadership who controls both the legislative agenda and party spending and fundraising for these members.

Case in point: by 2007, Congressman Shays was the last remaining Republican Member of Congress in New England (several others having been defeated when the majority shifted in 2006). He had for 20 years worked regularly worked with the same specific Democratic members on specific issues: One on energy, transportation and the environment; another on issues related to national defense and military intelligence; another on human rights and animal rights; yet another on financial services issues and on behalf of their many constituents to establish the 9-11 Commission, enact its recommendations and address many other concerns of the survivors; and so on. Those members were told personally, and then (if they ignored the admonishment) publicly in the Democratic Caucus by Speaker Pelosi to cease working with Shays or risk the chairmanship for which they were in line. The member who was the closest personal friend called Shays to apologize that they would no longer be able to work together because he had been told by the Speaker that he would not receive the chairmanship of the International Relations Committee, “for which I have worked my entire career,” if he did. The Member whose years of work on 9-11-related issues continued to work with him on those issues, and has never been elevated to the chairmanship for which she was in line.

The cost goes beyond legislation, too. Members (and staff) who cannot work together constructively on the day-to-day oversight and authorization process for federal programs -- designed to function outside partisan politics -- are rendered unable to perform their basic duties. This means that the day-to-day oversight function of Congress (not the “gotcha” hearings that so often make the headlines, but the workman-like review of federal programs that was the hallmark of the reauthorization process for decades ) is not done because the committees have so reduced their staff that they would not have the manpower to do it even if they remembered how. Case in point: The Investigative Subcommittee Congressman Shays chaired had seven staffers when he left office in 2009. It now has one, and its work is directed by the full committee. The result: an enormous percentage of federal programs are continuing on autopilot without authorization or review of any kind to identify what is working well and what is not; where there should be adjustments or improvements to programs and what should be reduced or eliminated. The cost to the taxpayer of this “savings” by Congress is likely in the billions of dollars.

SOURCE: Democracy Fund (democracyfund.org/idea/congress-and-public-trust-systems-map/)

Reduced institutional function -- exacerbated by money -- not only further undermines bipartisan working relationships but also reduces committee power. As leadership increasingly sets the agenda, the individual agency of Members is reduced almost to the point of nonexistence. This further sabotages capacity, Member satisfaction and public trust in the institution because they cannot move forward the initiatives they came to Washington to pursue -- through the subcommittee or committee markup process, in the Rules Committee or by amendment on the Floor.

A Cycle of Congressional Self-Loathing

Members respond to institutional underperformance with self-loathing, demonizing Washington and ironically running against the institution in which they seek to serve. By doing so they create a mandate for punishing themselves and further reducing the resources that enable their institution to function. This results not only in increased emphasis on messaging over legislation, but also in increased emphasis on ideology and increased staff turnover. All of this further reduces capacity for problem-solving, increases the potential for outside interest influence, and further reduces the ability of Members to process the demands they receive from the people they represent.

SOURCE: Democracy Fund (democracyfund.org/idea/congress-and-public-trust-systems-map/)

A case in point: While there was certainly some excess to trim and greater efficiency to be achieved, a cut of 22 percent in real dollars to Members’ Representational Allowances (MRA) meant that by 2014, the total MRA available to spend running an entire House office was equal to the total Betsy paid in staff salaries alone in 2008. As a result, the experienced, mid-level staff role paid $60,000 in 2008 was being filled by an equally talented staffer who could be paid only $40,000 by 2014. As importantly for the institution, the staffer who was making $60,000 in 2008 is still working on the Hill, as a chief of staff. The one making $40,000 left after 3 years and is working for the Beer Wholesalers lobby because he wanted to get married and start a family. But the institution has lost his experience and that of thousands like him; average staff age has fallen from 30 to 25 over the last 20 years, and an average staffer’s tenure is now under two years -- less than that of a Member’s term!

SOURCE: Democracy Fund (democracyfund.org/idea/congress-and-public-trust-systems-map/)

Media Matters

Finally, the map notes the accelerant role the media plays in all this. Democracy Fund has developed a separate systems map describing the state of media in general, but with regard to Congress, the media has experienced strains on its own resources that reduced coverage of the Hill for local communities beyond the most nationalized stories, making Congress seem less relevant and undermining public trust and satisfaction in the media as well.

When Betsy and her husband first came to DC, the National Press Building was filled with the Washington bureaus of more than 80 bureaus of local newspapers and TV stations who told stories of Members representing their constituents; why they voted the way they did; and held them directly accountable to the folks back home. Elimination of regional reporting, combined with the rise of the 24-hour news cycle and web-based news organizations, drives a constant need for stories that now pass as “news” to fill the bottomless news hole. And their inability to tell meaningful stories rather than write “gotcha” pieces further accelerates dissatisfaction and distrust

Systems Map published by Democracy Fund: https://democracyfund.org/idea/congress-and-public-trust-systems-map/